| Country: | United Kingdom |

| Period: | XX age |

Biography

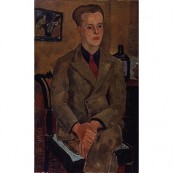

Leonard Constant Lambert (23 August 1905 – 21 August 1951) was a British composer, conductor, and author.

The son of Russian-born Australian painter George Lambert, Constant Lambert was educated at Christ's Hospital and the Royal College of Music. His teachers at the latter institution were Ralph Vaughan Williams, R. O. Morris and Sir George Dyson (composition), Malcolm Sargent (conducting) and Herbert Fryer (piano).[1] While still a boy he demonstrated formidable musical gifts. He wrote his first orchestral works at the age of 13, and at 20 received a commission to write a ballet for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes (Romeo and Juliet).

For a few years he enjoyed a meteoric celebrity, including participating in a recording of William Walton's Façade with Edith Sitwell.[2] Lambert's best-known composition is The Rio Grande (1927) for piano and alto soloists, chorus, and orchestra of brass, strings and percussion. It achieved instant success, and Lambert made two recordings of the piece as conductor (1930 and 1949). He had a great interest in African-American music, and once said that he would have ideally liked The Rio Grande to feature a black choir.

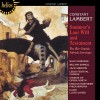

During the 1930s, his career as a conductor took off with his appointment with the Vic-Wells ballet (later The Royal Ballet), but his career as a composer stagnated. His major choral work Summer's Last Will and Testament (after the play of the same name by Thomas Nashe), one of his most emotionally dark works, proved unfashionable in the mood following the death of King George V, but Alan Frank hailed it at the time as Lambert's "finest work".[4] Lambert himself considered he had failed as a composer, and completed only two major works in the remaining sixteen years of his life. Instead he concentrated on conducting, and sometimes appeared at Covent Garden. To the economist and ballet enthusiast John Maynard Keynes Lambert was perhaps the most brilliant man he'd ever met; to Dame Ninette de Valois he was the greatest ballet conductor and advisor this country has ever had; to the composer Denis ApIvor he was the most lovable, and most entertaining personality of the musical world; whilst to the dance critic Clement Crisp he was quite simply a musician of genius.[5] But the respect of his peers could do nothing to help Lambert escape from his demons.

The Second World War took its toll on his vitality and creativity. He was ruled unfit for active service in the armed forces; decades of hard drinking had impaired his health, which declined further with the development of diabetes that remained undiagnosed and untreated until very late in his life. Lambert's childhood experiences (which included a near-fatal bout of septicaemia) had given him a lifelong detestation and fear of the medical profession.

An expert on painting, sculpture, and literature as well as music,[6] Lambert differed from most of his fellow English composers of the time in his acute and prophetic perception of the importance of jazz. He responded positively to the music of Duke Ellington. His embrace of music outside the 'serious' repertoire is illustrated by his book Music Ho! (1934),[7] subtitled "a study of music in decline", which remains one of the wittiest, if most highly opinionated, volumes of music criticism in the English language. Close friends of his included Michael Ayrton, Sacheverell Sitwell and Anthony Powell. He was the prototype of the character Hugh Moreland in Powell's A Dance to the Music of Time.

Lambert's father, while born in Russia and of American heritage, viewed himself as first and foremost an Australian. Constant was always conscious of his Australian connections, although he never visited that country. For the first performance of his Piano Concerto (1931), rather than select a British-born pianist, Lambert chose the Sydney-born, Brisbane-trained Arthur Benjamin to play the solo part. Despite his disapproval of homosexuality he formed a good working relationship with Benjamin's fellow Australian Robert Helpmann. Afterwards he entrusted yet another Australian musician, Gordon Watson, with the task of playing the virtuoso piano part at the première of his last ballet, Tiresias.[8]

As a conductor Lambert had an instinctive appreciation of Liszt, Chabrier, Émile Waldteufel and romantic Russian composers, most of whom were seldom heard in Britain before he championed them; he made fine recordings of some of their works. However, it was only from the late 1940s that the development of the BBC Third Programme and the Philharmonia Orchestra gave him the directorial opportunities with first-rank players which he craved. Before that he had long been relegated to the role of jobbing conductor, extracting vital performances from second-rate ensembles.