| 国家: | 匈牙利 |

| 期间: | Avant-garde |

传记

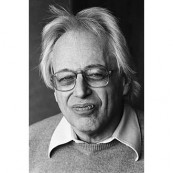

György Sándor Ligeti (Hungarian: Ligeti György Sándor [ˈliɡɛti ˈɟørɟ ˈʃaːndor]; 28 May 1923 – 12 June 2006) was a composer of contemporary classical music. He has been described as "one of the most important and innovative composers of the second half of the 20th century".[1]

Born in Transylvania, Romania, he lived in Hungary before emigrating and becoming an Austrian citizen.

Ligeti was born in Dicsőszentmárton, which was renamed Târnăveni in 1945, in Transylvania to a Hungarian Jewish family. Ligeti recalls that his first exposure to languages other than Hungarian came one day while listening to a conversation among the Romanian-speaking town police. Before that he hadn't known that other languages existed.[2] He moved to Cluj (Kolozsvár) with his family when aged six and he was not to return to the town of his birth until the 1990s.

Ligeti received his initial musical training at the conservatory in Cluj, and during the summers privately with Pál Kadosa in Budapest.

In 1940, Northern Transylvania was occupied by Hungary following the Second Vienna Award. In 1944, Ligeti's education was interrupted when he was sent to a forced labor brigade by the Horthy regime.[3] His brother, age 16, was deported to the Mauthausen concentration camp, and both of his parents were sent to Auschwitz. His mother was the only other survivor of his immediate family.[4]

Following the war, Ligeti returned to his studies in Budapest, Hungary, graduating in 1949 from the Franz Liszt Academy of Music. He studied under Pál Kadosa, Ferenc Farkas, Zoltán Kodály and Sándor Veress. He went on to do ethnomusicological research into the Hungarian folk music of Transylvania, but after a year returned to his old school in Budapest, this time as a teacher of harmony, counterpoint and musical analysis, a position he secured with the help of Kodály. As a young teacher, Ligeti took the unusual step of regularly attending the lectures of an older colleague, the conductor and musicologist Lajos Bárdos, a conservative Christian whose circle represented for Ligeti a safe haven, and whose help and advice he later acknowledged in the prefaces to his own two harmony textbooks (1954 and 1956).[5] However, communications between Hungary and the West by then had become difficult due to the restrictions of the communist government, and Ligeti and other artists were effectively cut off from recent developments outside the Soviet bloc.

n December 1956, two months after the Hungarian revolution was violently suppressed by the Soviet Army, Ligeti fled to Vienna with his ex-wife Vera (whom he was soon to remarry) and eventually took Austrian citizenship in 1968.[6] He would not see Hungary again until he was invited to judge a competition in Budapest fourteen years later.[7] On his journey to Vienna, he left most of his Hungarian compositions in Budapest, some of which are now lost; he only took with him what he considered to be his most important pieces. He later explained, "I considered my old music of no interest. I believed in twelve-tone music!"[8]

A few weeks after arriving in Vienna he left for Cologne. There he met several key avant-garde figures and learned more contemporary musical styles and methods.[9] These included the composers Karlheinz Stockhausen and Gottfried Michael Koenig, both then working on groundbreaking electronic music. During the summer he attended the Internationale Ferienkurse für Neue Musik in Darmstadt. Ligeti worked in the Cologne Electronic Music Studio with Stockhausen and Koenig and was inspired by the sounds he heard there. However, he produced little electronic music of his own, instead concentrating on instrumental works which often contain electronic-sounding textures.

After about three years' working with them he finally fell out with the Cologne School, this being too dogmatic and involving much factional in-fighting: "there were [sic] a lot of political fighting because different people, like Stockhausen, like Kagel wanted to be first. And I, personally, have no ambition to be first or to be important."[2]

From about 1960 Ligeti's work became better-known and respected. His best-known work include works in the period from Apparitions (1958–59) to Lontano (1967) and his opera Le Grand Macabre (1978). In recent years his three books of Études for piano (1985–2001) have become better-known through recordings by Pierre-Laurent Aimard, Fredrik Ullén, and others.

In 1973 Ligeti became professor of composition at the Hamburg Hochschule für Musik und Theater, eventually retiring in 1989. In the early 1980s, he tried to find a new stylistic position (closer to "tonality"), leading to an absence from the musical scene for several years until he reappeared with the Trio for Violin, Horn and Piano (1982). His output was prolific through the 1980s and 1990s. Invited by Walter Fink, he was the first composer featured in the annual Komponistenporträt of the Rheingau Musik Festival in 1990

However, his health problems became severe after the turn of the millennium. On 12 June 2006, Ligeti died in Vienna at the age of 83. Although it was known that Ligeti had been ill for several years and had used a wheelchair for the last three years of his life, his family declined to release the cause of his death.[10] Ligeti's funeral was held at the Vienna Crematorium at the Zentralfriedhof, the Republic of Austria and the Republic of Hungary represented by their respective cultural affairs ministers. The ashes were finally buried at the Zentralfriedhof in a grave dedicated to him by the City of Vienna.[11]

Apart from his far-reaching interest in different types of music from Renaissance to African music, Ligeti was also interested in literature (including the writers Lewis Carroll, Jorge Luis Borges, and Franz Kafka), painting, architecture, science, and mathematics, especially the fractal geometry of Benoît Mandelbrot and the writings of Douglas Hofstadter.[12]

Ligeti was the grand-nephew of the violinist Leopold Auer. Ligeti's son Lukas Ligeti is a composer and percussionist based in New York City.

![Ligeti - Concertos for cello, violin & piano [Ensemble InterContemporain]](http://static.classicalm.com/repository/composition-cover/small/26948-img1459943748548490.jpg)