传记

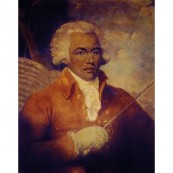

Joseph Boulogne, Chevalier de Saint-George (sometimes erroneously spelled Saint-Georges) (December 25, 1745 – June 10, 1799) was an important French-Caribbean figure in the Paris musical scene in the second half of the 18th century as composer, conductor, and violinist. Prior to the revolution in France, he was also famous as a swordsman and equestrian. Known as the "black Mozart"[1] he was one of the earliest musicians of the European classical type known to have African ancestry.

Great debate surrounds the accurate placement of Joseph Boulogne’s date of birth. Ranging from 1739 to 1749, the most widely accepted opinion asserts Joseph Boulogne was born on December 25, 1745 in Baillif, Guadeloupe, a Caribbean island.[2] Son of Nanon, a Wolof former slave, and Georges Boulogne de Saint-George, a white French plantation owner, Joseph acquired the name de Saint-George, after one of his father’s properties. Some biographers have mistaken his father for Pierre Tavernier-Boulogne, Controller-General of Finances, whose nobility dated back to the 15th century, but Joseph was not of this lineage. The confusion surrounding the nobility of Joseph Boulogne’s father originated with Roger de Beauvoir’s novel of 1840 ("Le Chevalier de Saint-George"). However, Joseph’s father Georges Boulogne was not ennobled until 1757, when he acquired the title of Gentilhomme Ordinaire de la Chambre du Roi (Member of the Royal Guard), and this noble rank was hereditary only for children born in wedlock.

Still young and living in Guadeloupe, Boulogne began studying the violin under Joseph Platon, a skilled violinist of color.[3] (Platon would later play an unspecified Saint-George violin concerto at Port-au-Prince (Haiti) on April 25, 1780.) Eventually driven by his father’s ambition to raise his son to the heights of the aristocracy, Georges Boulogne moved with his family to Paris in 1749, where Joseph would begin his proper education. After a few years living in Paris, at age twelve, Boulogne participated in his first fencing match, demonstrating potential for the sport. Drawing attention to himself, the following year Boulogne became a student of La Boëssière, the master of arms, and excelled at the sport, eventually helping to bring recognition and renown to his teacher. In fact, while enrolled, Boulogne proved to be a skilled student in not only the physical facets of boxing, fencing and riding, but also creative ones, coming into his own as a violinist.[4] Francois-Joseph Fetis, a Belgian composer born late in the 18th century noted that as early as age 10, Boulogne “was already surprising his teachers with his facility for learning.”[5]

His fencing master, La Boëssière, best describes Boulogne’s progress through his adolescence: “At fifteen[…] his progress was so rapid that he beat the best swordsmen. At seventeen he had acquired the greatest speed. In time, he combined with his prompt execution an expertise that finally made him without peer.” “Saint George had grown to a height of five feet ten inches. He was very well built, with a prodigious strength of body and extraordinary vigor. Lively, supple, and slender, he astonished everyone with his agility. No one in the class showed more grace, more consistency.”[6]

Alongside his physical training and classical education, Boulogne was also a student of some of the most revered musicians in Paris. Jean-Marie Leclair (1697-1764), the brilliant violinist, and Francois-Joseph Gossec (1734-1829), the skilled composer, took Boulogne under their wing, recognized the great musical potential he possessed, and began to cultivate it. In 1761, upon completion of his education, Boulogne was made Gendarme de la Garde du Roi.

Even in his adolescence, Joseph Boulogne displayed talent beyond his abilities as a fencer. Exhibiting virtuosic ability on the violin, Boulogne would often “establish themes in different tonalities to the ceaseless delight of his listeners.”[7] He was the first violinist for La Popliniere’s orchestra, under the direction of his composition teacher, Francois-Joseph Gossec (1734-1829).

Just as he had with his fencing, Boulogne’s virtuosity began to draw the attention of other musicians and at this time he was often challenged to musical duals, overpowering many in dexterity and expression with the bow. Some musicologists speculate these competitions greatly influenced his composition in the concertante style later in life.

In 1764 Boulogne’s violin instructor, Jean-Marie Leclair, was murdered in front of his home. This left room for an up-and-coming violinist, like Boulogne, to take LeClair’s stead. At this point in his career, Boulogne was clearly mastering his instrument, garnering affection and musical dedications from others, including his teacher Gossec.[8]

In his own six trios (opus 9), Gossec writes: “To M. de Saint George, equerry, Gendarme of the King’s Guard. Sir, The fame which you have acquired by your talents and the favorable welcome that you have extended to artists, have encouraged me to take the liberty of dedicating to you this work, as an homage due to the merit of such an enlightened lover of the arts. If you give it your vote, it will have certain success. I am, Sir, respectfully, your very humble servant.”[4]

In 1769 Boulogne became a member of Gossec’s new orchestra, the Concert des Amateurs, immediately holding the positions of first violin and timekeeper. Standing front and center during every performance, Boulogne was thrust into the public eye, inciting an enthusiastic response. By 1773, he would take over charge of the ensemble and hold the respected position for eight more years.

At the same time, Boulogne’s first compositions were also received by the public, and often showcased at the Hotel de Soubise. He first composed for string quartet, but soon expanded to a full 76-instrument orchestra, utilizing his Concert des Amateurs as a testing ground for his works.[9]

In respect of his skill as both a composer and musician, Boulogne was selected for appointment as the director of the Royal Opera of Louis XVI. Despite his position as the only eligible applicant, Boulogne was refused, prevented by three Parisian divas who petitioned the Queen. Writing against the appointment, the trio insisted it would be beneath their dignity and injurious to their professional reputations for them to sing on stage under the direction of "a mulatto".[10]

As a member of the aristocracy and the royal court at Versailles, Boulogne served in the army of the Revolution against France's monarchist enemies. An amateur in war apart from his fencing past, Boulogne took command of a regiment of a thousand colored volunteers. Despite military success, he was repeatedly denounced because of his aristocratic parentage and past association with the royal court, and Boulogne was dismissed from the army on September 25, 1793 and imprisoned. He was acquitted after spending 18 months in jail.[11] After the revolution, Boulogne continued to lead orchestras but struggled to find his place in a France very different from the indulgent aristocracy he was accustomed to. Resigned to the life of a commoner Joseph Boulogne died in 1799 at the age of 54, falling into obscurity.

As Joseph Boulogne aged, he focused less on his fencing and more on music. A musician with an attractive talent to express the underlying emotions written into the classical galant style of the time, Boulogne emerged into the French aristocracy as a virtuoso and skilled composer.[13]

The Virtuoso

Many believed that Boulogne’s skill leapt from his sword to his violin bow. Performing throughout France and even in London, Boulogne became very well known for his rendition of “The Loves and Death of the Poor Bird,” and was often asked to perform it. A singer, Louise Fusil, most devoted to Boulogne, records in her memoirs: “Saint-George had a feeling or music to the highest degree, and the expressiveness of his execution was his principal merit.”[14] As a violinist, Boulogne often held the position of first violin and timekeeper; a testament of his skill and the respect his talent garnered from his peers.

The Composer

By 1765, Boulogne had begun work on his first compositions, but this work would not be published for another eight years. Trained by Gossec, Boulogne wrote in the classical galant style similar to that of his contemporaries, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Joseph Haydn. In fact, at the peak of his career, the works Boulogne and Mozart often shared a billing, alternating as the evening program. Fueled by his own virtuosity, Boulogne wrote scores that challenged the abilities of his musicians and frequently asked violinists to take flashing leaps from the top to the bottom of their range.[15] It is believed that a mere third of all of his compositions are known today. The rest either remain undiscovered, or were lost in the fires of the French revolution.